In this series, I'm sharing some excerpts from my book, “Practical Paleo” with you.

You may or may not choose to follow a paleo style of eating, it isn't required to be healthy. But, many of you have told me you've benefitted from eating paleo for a short or long period of time, so these posts will explain more of the premise behind paleo eating for those curious.

Further, while I don't currently educate publicly about the paleo diet, you can always read a lot more and get over 100 easy paleo recipes in “Practical Paleo.”

Here's what the USDA has to say about legumes in our diet…

“A healthy eating pattern includes a variety of vegetables [including] legumes (beans and peas).”

“A healthy eating pattern includes a variety of protein foods, including . . . legumes (beans and peas).”

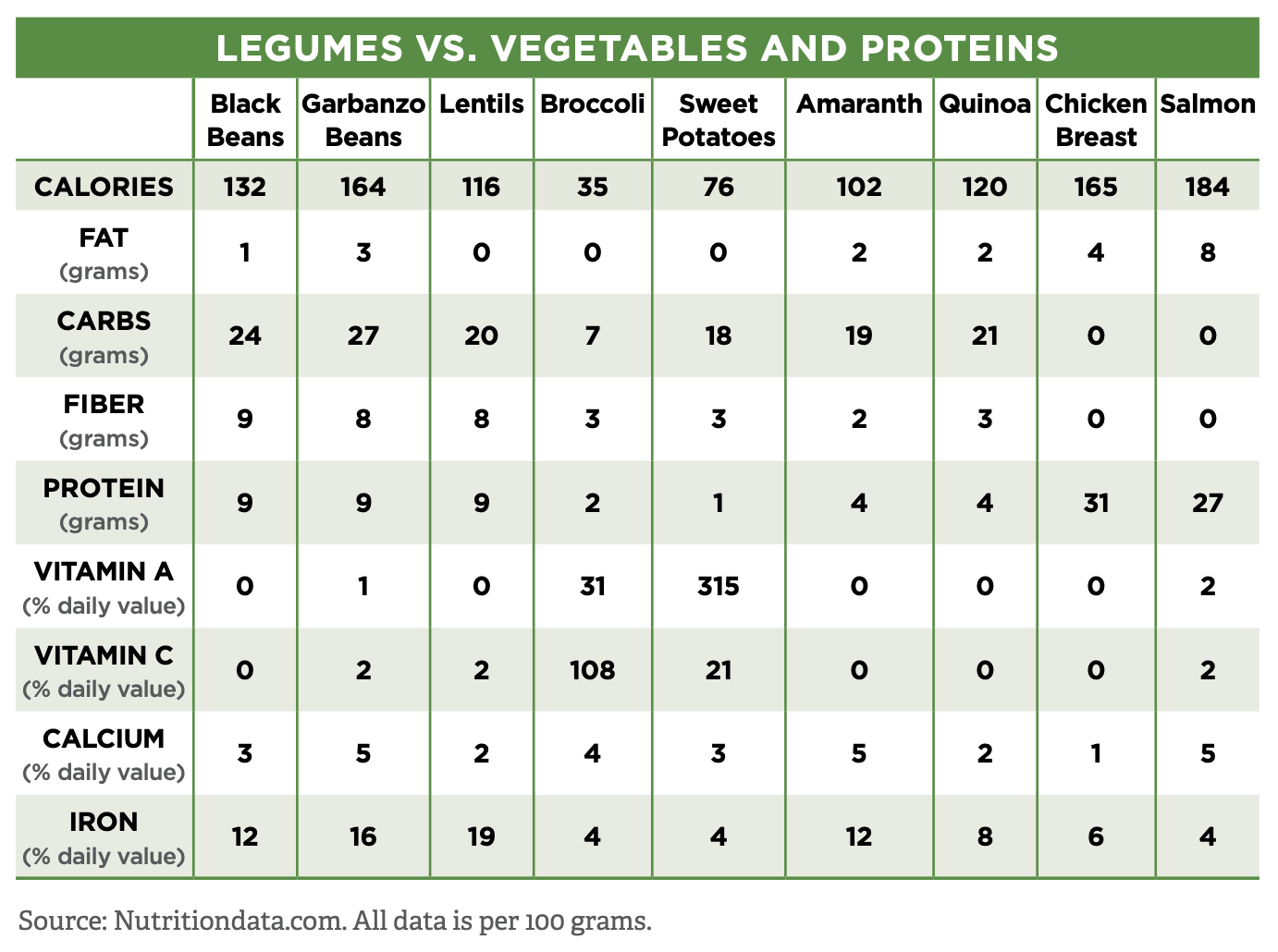

The USDA categorizes legumes (beans, including soy, peas, and lentils) as both vegetables and a source of protein, but legumes are truly neither of these. Nutritionally speaking, legumes are a lot more like grains than they are like any vegetable or true protein source. A quick look at the nutritional breakdown of some commonly consumed beans and lentils compared to some common vegetables and protein sources shows exactly what I mean.

As you can see, while beans and legumes do have slightly more protein than vegetables like broccoli and sweet potatoes, they have nowhere near the protein density that chicken and salmon deliver.

Legumes should be treated much more like a grain than either a protein source or a vegetable in terms of their recommended consumption. And, in my estimation, this means that they should either be eliminated entirely (to follow a strict Paleo diet) or limited to very small portions, since they’re not as significant a source of vitamins and minerals as vegetables, nor as significant a source of protein as animal foods.

But there’s a study that says . . .

In nutritional research, most studies are epidemiological, which means they look

In nutritional research, most studies are epidemiological, which means they look

at patterns and correlative information in groups of people. Discovering a correlation does not provide evidence of any causation, though. It simply means that two factors seem to be related, but it doesn’t take into account every other variable involved. For example, while you may see people carrying umbrellas when you also see rain falling, you’d never say that carrying an umbrella causes rain to fall.

Unlike epidemiological nutrition studies, randomized, controlled trials in metabolic wards—where all food given to test subjects is carefully measured and recorded—can be used to discover direct cause and effect. That’s the solid scientific evidence that nutritional advice should be based on. The problem is that most studies that result in broad, sweeping (and often sensationalized) nutrition news headlines are epidemiological, not randomized, controlled trials.

An even bigger problem is that epidemiological studies are based on “dietary recall,” in which subjects remember and record their daily diets, going as far back as several years. Let’s get real! Do you remember what you ate last year? Last month? Last week? Even yesterday? Obviously, claims based on dietary recall are far from science.

When you see broad nutritional recommendations without actual biological explanations, you can assume that they’re derived from evidence reported in an epidemiological study using dietary recall as the source. Run the other way.

If you missed the intro to this series, you can find it here.

Last week I shared about the USDA Recommendation for Grains. Stay tuned for The Recommendation for Dairy coming next week as well as my follow-up posts with my own recommendations.

Comments 1

Pingback: What We've Been Fed: The Recommendation for Dairy | Balanced Bites | Squeaky clean heat-and-eat meals | Organic Spices | Created by Diane Sanfilippo